Phishing Attacks

Phishing is one of the most common ways ransomware seeps into a network. As an attack technique, its popularity is probably fuelled by its success. Ransomware operators directly or indirectly compromise networks with phishing by either sending the emails themselves or purchasing pre-phished victims (known as access for sale) from other hackers. In both cases, one or more of the below tactics will probably be employed:

Credential phishing

Phishing for credentials is the art of tricking users into clicking a link, eventually leading to a fake but convincing login page where users willfully hand over their username and password combination, which attackers use to log in to a victim's network or service.

The proper prevention (or at least speed bump) for this phishing format is enforcing two-factor authentication on all user accounts without exception.

Enforcing 2FA makes it hard (but not impossible) for a stolen password alone to allow accounts to be compromised because 2FA is made up of something you know and something you have. The "something you know" is a password, and "something you have" is often a code generated on a smartphone app. The "something you have" part of 2FA lets us confidently confirm that the person authenticating is who they say they are.

As with all security solutions, 2FA isn't a silver bullet that magically stops account takeovers entirely. Modern phishing campaigns can intercept 2FA authentication traffic via Man In The Middle Phishing, which places a transparent proxy between the victim and the service or system they are authenticating to. The proxy steals 2FA tokens and replays them to the target service before they rotate, then passes the authenticated session cookie back to the attacker, who can control the now logged-in session under their victim's account.

Image credit: https://catching-transparent-phish.github.io

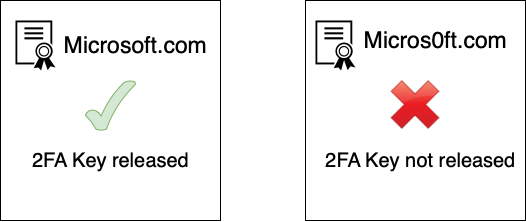

The current best form of 2FA, which is resistant to man-in-the-middle phishing attacks, is to provide users with physical security keys that are FIDO2 compliant. The FIDO standard stores a certificate inside a small physical USB device. The certificate inside these keys is tied to a particular domain, meaning it will only enable login if the user has landed on the domain they should be logging into. For example:

Unfortunately, the adoption of FIDO keys has been slow partly because of the complexity and cost but mainly because support for physical security keys is patchy. Many security experts recommend using them, but at the time of writing, Microsoft 365 and many other services only support using keys in specific desktop-based browsers, meaning legacy 2FA like one-time codes still have to be enabled. Microsoft, for example, supports FIDO2 keys in Chrome on desktop but not in any of their smartphone apps like Outlook or Teams, which leaves a pretty gaping hole.

Big tech is working towards standardisation and ease of use, which should accelerate the adoption of physical security keys. Over the next few years, we should see the barrier to entry lower thanks to standards like Passkeys and Webauthn, which enable our smartphones to themselves become physical FIDO keys. Until then, all administrators must enable some form of two-factor authentication, FIDO or not.

All major vendors offer 2FA for their services, but not all second factors are created equally! Administrators should ideally avoid all one-time code-based systems (which include SMS, apps that generate codes and automated phone calls) because these, just like passwords, can be stolen via the aforementioned man-in-the-middle phishing. We must use the second factors, which involves challenge and response. Azure and Google Workspace offer modern solutions which require users to approve a push notification on their smartphone. Although once again, these push notifications can be beaten with attacks like MFA Fatigue which spam a user constantly with login authorisation notifications until they give in and approve access.

In Microsoft Azure/O365, administrators should ensure number matching 2FA" is enabled for all user logins. Number matching adds a choice of three numbers to each login 2FA prompt, making it very difficult for an attacker to phish a one-time code or perform a fatigue attack successfully.

Whatever path you decide to take, ensure 2FA is enabled for authentication and avoid one-time pins. Also, make your user experience comfortable, don't make them constantly authenticate throughout the day, and ensure your maximum session time is reasonable.

Malicious Links

Access brokers and ransomware operators enjoy delivering malicious links to users via email. Most of the time, the attacker will try to link the user to a website that downloads a malicious file, but more advanced actors will try to exploit vulnerabilities in browsers or operating systems.

DNS filtering and URL rewriting combat phishing by preventing users from loading a malicious page even if they click a bad link. It is impossible to block all link-based phishing, but it is possible to reduce the risk. Link filtering is most commonly implemented by using a URL gateway that scans links in emails as they are delivered, but there are plenty of other methods available.

Most DNS, URL and email filtration software will offer protection as standard. Tools like Mimecast, Proofpoint, Microsoft E5 and Cisco Umbrella can prevent malicious links from loading.

If your business does not have a good email security gateway or the appetite for new technology and the associated bills, you can look for cheap or free alternatives. The protection that free tools offer is not as adequate as their enterprise-grade cousins, but that doesn't mean they shouldn't be used. If you haven't got a budget for enterprise tools, then installing something is better than nothing.

Browser extensions like Malwarebytes browser guard are a decent and free option that can be deployed quickly. Addons-like browser guards help prevent your users from opening known malicious pages.

DNS filtering is another excellent method for filtering bad links and, in some cases, for cheap or free. Passing all DNS queries through a service like Cisco Umbrella is a powerful way to prevent users from landing on suspicious and malicious websites. Even more straightforward is simply switching to a DNS provider that blocks malicious domains upstream. The OpenDNS project is simple to implement and free. Changing your upstream provider to OpenDNS could help block phishing and other scams.

In an ideal world, your email gateway should scan links in the body of incoming emails and block anything it deems malicious. Allowing users to interact with unchecked links is extraordinarily risky and leaves protection down to the user endpoint and whatever agent is running there. If using an email gateway is out of the question, consider implementing one of the cheap or free options mentioned earlier.

Malicious Attachments

Modern attackers successfully breach targets by sending malicious attachments directly to their victims. In most cases, the payload is hidden inside a Microsoft Office document disguised as legitimate business mail. A malicious attachment will sometimes need further user interaction before being able to execute code. Still, in some rare cases where a zero-day or unpatched vulnerability is involved, no user interaction is required.

Macros in office attachments are an extremely popular attack vector, and as such, you should concentrate some effort on blocking or preventing them from reaching your users. If your business isn't using macros or never receives them via email, it's a great idea to disable them altogether. Block the file type.XLSM from being delivered at all and disable macros via group policy. If your business need macros, you can wrap some controls around them with a group policy. The Disable Internet Macros group policy prevents executing a macro delivered from the internet or via email. If you do anything from this entire body of information, do this. Disable Macros. Cyber security professionals want you to. No, really, we do.

Macro-based infections have become such a problem that Microsoft is disabling external macros by default, but users can still bypass the block, although they must go out of their way to do so. Again, if your business doesn't need macros, block them from executing entirely but bear in mind; security policy should work with a business and not against it, do not force a macro block on staff that have a legitimate business reason for using them, you should be enabling your business to function securely not locking them down unnecessarily.

The Microsoft ecosystem has countless file types that can execute malicious code; some of them probably aren't even discovered yet, so controlling macros isn't the endgame. There are still plenty of other paths to monitor and isolate, but far too many for a standard IT team to get their hands around. As such, acquiring a modern endpoint detection and response is a good idea. EDR is a powerful way to monitor systems for malicious files and their activities regardless of where they came from, email or otherwise.

Despite marketing material, no tool will ever give you 100% protection, but EDR will provide you with dramatically better protection than standard antivirus.

Traditional antivirus looks for file hashes that act similarly to a policeman looking for fingerprints; if the antivirus doesn't recognise the fingerprints of a piece of malware, it can't detect it. On the other hand, EDR looks for suspicious behaviour which means it can detect malware regardless of how it looks and feels or if it's seeing a piece of malware for the first time. For example, if a brand new piece of malware (or dangerous attachment sent via phishing) makes it into your network, your EDR tool should be able to detect the attack by the parent-child process relationship. In the below-simplified example, we see Winword.exe as the parent of Powershell.exe, which is a strong indicator of malicious behaviour often delivered by attackers.

EDR tools are a good final layer against phishing attacks which have made it through your other layers of defence, although they can be costly and time-consuming to deploy. Later in our documentation, we have a section dedicated to finding and selecting an EDR tool.

Summary

- Attackers use links to drive users towards forms which can steal credentials and 2FA codes. Apply URL filtering at the email gateway, DNS monitoring or an endpoint agent to help combat phishing links.

- Enable 2FA for every single user, avoid using One Time Codes if possible. On O365 ensure “Number Matching” is enabled.

- Be sure your email gateway scans attachments and has our block list in place.

- Deploying an EDR solution is the last line of defence against phishing emails that make it through to users.